Where "Meaning-Free Distinctiveness" Jumped the Shark

The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute takes their prescription too far. Here's what brands can do instead.

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of Woo Punch, a brand design studio rooted in marketing science.

Currently seeking new design and naming projects.

The Idea That Divided Marketing: Meaning-Free Distinctiveness

In 2010, Byron Sharp and the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute (EBI) introduced meaning-free distinctiveness (referred to as meaningless distinctiveness at the time) in How Brands Grow: What Marketers Don’t Know.

Forget purpose, differentiation, or epic storytelling. EBI said shoppers buy what they recognize, not what moves them. Brand assets—logos, jingles, mascots, colors—shouldn’t mean much at all, just point straight to the brand. Recognition beats interpretation. And they argued that this “meaning-free distinctiveness” is far more powerful for brand growth than the old pursuit of “meaningful differentiation,” which, while real, does little heavy lifting. EBI didn’t just talk smack; they backed it with data that made everyone squirm.

Consumers operate on efficiency. They spot a familiar cue, pick the product, and keep moving. EBI handed us a ruler (assets that scream one brand only in any context) and a recipe (keep ’em “blank slates”). The measurement logic holds: assets work best when the brand itself carries all the meaning, even outside the category. That’s the target—100% ownership—even if no brand ever reaches it. Some confusion always lingers, even for the Nike swoosh or Coca-Cola script. The goal is maximum dominance.

Meaning-free distinctiveness is an empirical measurement outcome and a useful benchmark. The flaw lies in EBI’s creative prescription: it sometimes treats “blank slate” as design guidance for new assets, rather than the earned end-state of dominant ones.

That’s where they jumped the shark.

The Trouble with “Meaning-Free” in Practice

After Byron Sharp introduced the idea in How Brands Grow, his colleague Jenni Romaniuk explored it further in Building Distinctive Brand Assets (2018). She writes, “The brand wants assets that evoke little (other than the brand name)—the blanker the slate, the easier it will be to make your brand a memorable part of the asset’s network for category buyers.”

Romaniuk illustrated the idea with Pringles:

“If I see the [Pringles] man and associate him with being Italian… I might remember Pringles, or think of Italy… pasta and so on.”

In 2022, she clarified the concept in Contagious:

“A meaning‑free asset is one where the strongest meaning is actually the brand. … If you have something that already has a strong meaning, the brand is constantly fighting that old meaning.”

Most recently, in Marketing Week (2025), she used Lancashire Tea’s rose logo to make the same point:

“Seeing an image of a rose reminds you of the fabulous Michael Douglas/Kathleen Turner War of the Roses movie… and… you fail to register the Lancashire Tea brand sitting next to the rose image.”

These examples illustrate a valid measurement point—strong existing associations dilute brand ownership. Presented as design rules, however, they assume shoppers conduct mental detours in the aisle. But grocery aisles aren’t therapy sessions. Nobody pauses mid-shop to free-associate prior Italy trips or Michael Douglas movies. Recognition happens in a blink.

To me, meaning isn’t the problem—category meaning is. When every brand in a category already carries familiar cues, brands blend together. Banks use blue to signal trust. Dairy uses cows. Coffee shops use earth tones. Distinctiveness is an afterthought.

Looking for a distinctive and timeless brand? I’m currently open for design and naming projects.

Enter Category-Defiant Distinctiveness (CDD): Flip the Script, Own the Shelf

The goal isn’t to avoid meaning—it’s to avoid the kind that makes you disappear: to defy your category and stand out. That’s what I call Category-Defiant Distinctiveness (CDD): names* and assets deliberately built to defy category meaning. It bridges EBI’s measurement logic for existing assets with the creative challenge of building memorability from scratch.

*Note: Although EBI’s research focuses on assets like logos and colors, the principles—distinctiveness before meaning—can inform how brands approach naming. Names, like assets, benefit when they stand out relative to category norms, even if names can’t be measured in the same way as assets.

The concept is best understood by its opposite: category-natural cues. A waterfall logo, for instance, is category-natural for a water brand. By contrast, a waterfall logo for a car insurance brand is Category-Defiant. While this is an obvious example, category-natural cues can also include style, tone, or subtle cultural elements. Fiji Water’s hibiscus evokes nature and purity, fitting the category without being literal. On its own, it might have blended in—but paired with Fiji’s distinctive bottle shape, it becomes unique.

The practical application of Category-Defiant Distinctiveness involves a simple rule: raid your rivals to torch the patterns. Scour every competitor’s name, logo, and color, and actively reject those common traits. Only after this critical step can you use meaning to name a brand or design a unique brand asset. Then, cross-check every idea against those category patterns to ensure you always avoid them at all costs.

Achieving CDD doesn’t demand extremes like Liquid Death. Acqua Panna’s fleur-de-lis and S.Pellegrino’s star succeed with assets that are unexpected in their categories but still feel authentic for their brands. CDD can exist on a spectrum.

A Spectrum: Category-Natural → Category Defiant

The point is that meaning can’t—or shouldn’t—be avoided entirely. Symbols with rich cultural meaning can even strengthen a brand’s distinctiveness when used cleverly within its category.

John Deere and Apple are prime examples of Category-Defying Distinctiveness using symbols rich with cultural meaning. Deer are highly symbolic, but a deer made no sense for heavy machinery at the time. It wasn’t symbolic; it was simply distinctive. Meaning was built around it later (i.e., “Runs like a Deere”). Apple did the same thing. Apples are rich with symbology, but an apple in tech was nonsense, which was why it worked. The name wasn’t symbolic when it was conceived in 1976;* it was just disarmingly out of place.

EBI’s gold standard as a measurement outcome is a solid goal: for your assets to get recognized even outside your category. The problem lies in translating this finding into a creative prescription.

Most brands will never achieve the global, out-of-context fame of Apple, whose logo is instantly recognized and correctly attributed even on the back of a car window, completely removed from the context of computers or phones. However, high distinctiveness within the context of the category is more achievable and highly effective. EBI’s insistence on a “blank slate” overreaches, treating an ideal end-state as an initial design requirement.

Meaning-free distinctiveness sets the bar; Category-Defiant Distinctiveness builds the ladder to reach it.

*Despite endless lore about how Steve Jobs chose the name Apple—and how he later backfilled meaning into it with the Isaac Newton logo—the truth is simpler.

According to Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, Jobs said he “had just come back from the apple farm.” The name, he explained, “sounded fun, spirited, and not intimidating. Apple took the edge off the word computer—plus, it would get us ahead of Atari in the phone book.” He told Wozniak that if a better name didn’t hit them by the next afternoon, they’d stick with Apple—and they did.

The Tyranny of Meaning-First Design

Most brands crash because designers swoon over purpose and “perfect customers,” convinced meaning fuels growth. But shoppers can’t buy your saga if they don’t know you exist. Names and Distinctive Brand Assets (DBAs)—logos, colors, mascots—are brain hacks answering: “Who’s this from?”

This obsession with meaning—what I call brand strategy theater—often undermines the single most important thing that makes a brand stick: distinctiveness. Recognition leads; meaning tags along.

Why Brand Names & Assets Built On Differentiation Are Ticking Time Bombs

Brand names and assets built around differentiation are unstable. Differentiation can change; distinctiveness shouldn’t. Meaning and differentiation certainly have their place, but tying them to names or assets is risky.

Category Entry Points (CEPs) make this obvious. A CEP is any context that makes a consumer think about a category before brands enter the picture. A small business owner sending a newsletter is a CEP for “marketing tech.” A new CMO analyzing customer data is another.

Brands need their names and assets to work across every relevant CEP. In other words, names, logos, mascots, or other distinctive assets must be adaptable to any context. Differentiators often fail here. They can be context-dependent and may box brands in as they grow.

Differentiators flop in two epic ways when they’re treated as the north star for naming and design:

Blending In: Many differentiators are category-natural—predictable and easy to copy. A chiropractor using a lotus to signal wellness may seem different from one specializing in sports medicine, but wellness signaling is common, so it still blends in.

Boxed In: Anchoring assets to a differentiator limits growth. MailChimp launched as a simple email tool—a clear differentiator early on—but its name remains tied to email, limiting its ability to expand into broader marketing tech services. Monster Energy’s hyper-masculine identity works for some audiences and settings but falls flat in others—it appeals mainly to men and can feel out of place in professional contexts. Red Bull, by contrast, pairs a masculine name with playful, minimalist design and whimsical animations, letting its assets flex across audiences and situations. Category-Defiant Distinctiveness ensures the brand works in any context.

I asked AI to generate an image of a “typical Monster drinker” from this Vice article. According to the same article, “The ‘classic Red Bull drinker’ is hard to pinpoint because it’s the most standard of energy drinks…. The Red Bull drinkers are everywhere among us, everywhere, but nobody knows exactly who they are.”

In short: differentiators fade, features blur, meaning shifts. Distinctiveness endures.

Distinctiveness: Differentiation’s Wingman

Meaning and differentiation aren’t irrelevant—they’re just harder to earn than most marketers admit. Differentiation is rare, costly, and fragile. Even giants never truly “own” a unique differentiator. The most successful brands achieve what Mark Ritson calls “relative differentiation”—just different enough relative to competitors in the buyer’s lens. Volvo is a bit safer than Toyota, Walmart is cheaper than Target, Apple is more fashionable than Samsung. Distinctiveness cements those tweaks in memory.

Marketers miss this when they treat distinctiveness and differentiation as enemies. Distinctiveness doesn’t replace meaning or differentiation—it supports them. It glues relative differences to the brand so they can be recalled later. Meaning isn’t the starting point; it’s a by-product of consistent, distinctive exposure.

Making Category-Defiant Distinctiveness (CDD) Sing: Strategic Filters and Safety Checks

Category-Defiant Distinctiveness doesn’t mean randomness. Unique names and assets still need checks to ensure they’re not just recognizable, but also work—clear enough to be understood and appealing enough to be liked. Distinctiveness without clarity confuses; distinctiveness without appeal repels.

You have to link the “out-of-place” to the right context so it’s both recognizable and clear. That connection doesn’t have to live inside the name or asset itself (a chiropractor doesn’t need a spine in their logo). Often, it comes from the surrounding context—how, where, and alongside what the brand shows up.

Two sets of filters make that happen: Category Identifiers, which ensure clarity, and Aesthetic Fit, which ensures the brand still feels right.

Category Identifiers: Ensuring Clarity

Every CDD asset must be paired with Category Identifiers—context that signals what the brand actually sells. Distinctiveness = “Who?” Identifiers = “What?” You need both.

Achieving close to 100% recognition outside any category context, like an Apple sticker on a car window, is less of a practical benchmark and more a fantasy—the branding version of a glittery dream board with a picture of you and a magazine cutout of Johnathan Taylor Thomas. 99.9% of brands will never come close.

Still, customers are distracted. Even if the category feels obvious to you, Category Identifiers are crucial for comprehension—some are designed deliberately, others come baked into the context.

Category Identifiers can take several forms:

Baked-In: Default context clues. An elephant on an ice cream carton, sitting alongside other ice cream brands, still reads as ice cream. A donkey under a gas station canopy still reads as fuel.

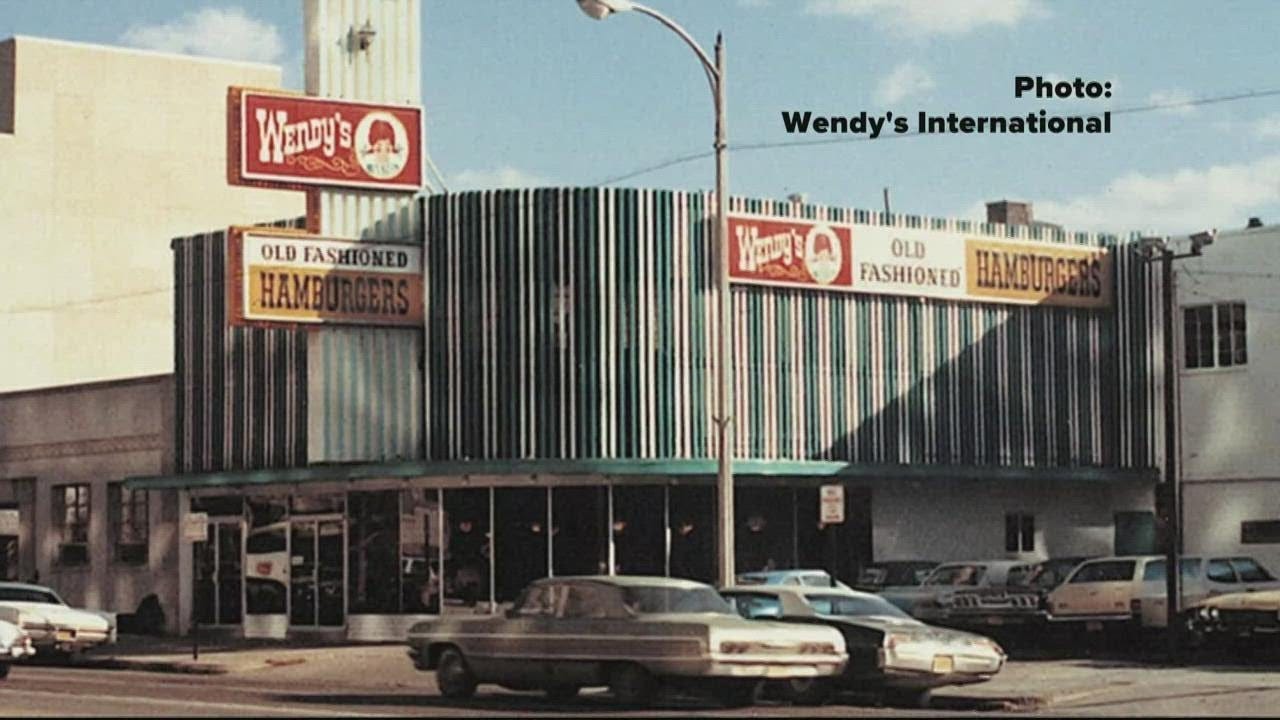

Added for Clarity: Supporting copy, descriptors under a brand name, or signage. Wendy’s red-headed girl, for example, was paired with a sign reading “Old-Fashioned Hamburgers” early on. If a women’s clothing boutique is named LampLight, the sign should include something like “Women’s Clothing Boutique” or “Women’s Fashion” so customers don’t mistake it for a lamp store.

Note: Ensure the descriptor is large enough and legible enough to read. I see local shops in my town mess this up all the time.

In-Use Context: Advertising the asset in use or in an explicit category environment, like the Snuggle bear inside a laundry basket on TV.

When paired with the spectrum of category-natural to Category-Defiant, these checks let brands push boundaries without losing comprehension. The further an asset leans toward Category-Defiant, the more it benefits from clear category cues to ensure recognition doesn’t come at the expense of understanding.

Baked In: Early Shell gas stations had a giant shell, which would have been confusing if it wasn’t paired with gas pumps.

Added For Clarity: One of the first Wendy’s locations featured a Category-Identifier nearly as large as the restaurant’s own name.

In Use Context: This cuddly little guy was always seen playing inside laundry baskets and snuggling with clothes.

Aesthetic Fit: Feel-Good Strangeness

Beyond category clarity, assets need to feel right to consumers and maintain a loose fit with the brand, or they risk turning people off or distracting from what the brand actually does. Category-Defiant Distinctiveness isn’t chaos—it’s controlled strangeness.

Well-designed names and assets balance distinctiveness with “feels right.” Associative undertones can reinforce without blending.

Example: Domino’s name and logo loosely fit the pizza category—they’re playful without being direct. But a domino wouldn’t work for a funeral home.

Three deeper filters help assets succeed:

Affective Association: Assets should generate positive affect. If a cue is too jarring, unpleasant, or off-putting, it fails to trigger the subtle System 1 signal that tells people, “I like this.” Even when an asset looks different from the category norm, it should still feel pleasing and enjoyable.

Loose Fit Across Brand, Category, and Customer: CDD assets can—and often should—carry implicit meaning that supports the brand, as long as the core idea remains Category-Defiant. Meaning doesn’t have to be explicit; it can be associative, aesthetic, or cultural, giving assets a familiar undertone without letting them blend in.

Avoid Confusion With Other Categories: Even the boldest CDD assets can backfire if they’re already claimed by a dominant brand in another field (e.g., a talking gecko for a soda brand could easily get confused with Geico), or by an entire category (e.g., a roof logo for a lawyer might still read “real estate” on a billboard).

The Point of All This

EBI’s work gave marketing the right measuring stick but the wrong creative brief. Meaning-free distinctiveness is useful as a diagnostic tool, not a design philosophy. It tells you how well your assets are recognized, not how to make them.

The mistake is thinking you can design a blank slate from scratch. You can’t. Distinctiveness is earned through exposure, not engineered through emptiness. Designers who start with “no meaning” end up with nothing memorable.

Category-Defiant Distinctiveness flips that script. It says: build assets that break your category’s conventions but still fit the brand. Be strange in the right way.

Meaning will come later, whether you want it to or not. The job isn’t to avoid it—it’s to make sure it forms around you instead of your category. That’s how you move from theory to practice, from measurement to memory.

Meaning-free distinctiveness is the destination. Category-Defiant Distinctiveness is how you get there.

For more thoughts on brand design, advertising, and marketing, you can find me on LinkedIn.

Brilliant. Thank you. I am working with a brand that has symbol in their logo which is the same as almost every other competitor in their sector. This helps my discussions about the challenges with that and a potential approach to change.