Design Has a "Brand Strategy" Problem.

How a Fixation on Strategy is Distracting Designers and Hurting Businesses.

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of Woo Punch, a brand design studio rooted in marketing science.

Currently seeking new design and naming projects.

In seventh grade, my basketball team went 0-15. We spent so much time obsessing over complex plays on the whiteboard that we forgot the basics: dribbling, passing, and shooting.

I fear the design industry is making the same mistake.

We’ve abandoned the fundamentals of distinctive and timeless design to chase “brand love.” Designers are now expected to act as “brand strategists,” leading endless “design sprints” filled with personas, archetypes, and “onliness statements.” Meanwhile, creating truly distinctive and enduring brands has taken a backseat—all under the banner of “brand strategy.”

We mistake genuine brand strategy (essential for marketing success) for the design world's “brand strategy theater”—a mere performance of strategic rituals that prioritize the illusion of strategic depth over the fundamental principles of brand design.

This obsession with strategy, inspired by texts like Marty Neumeier’s The Brand Gap and promises of a “brand love” utopia, has steered us off course. It values theory over execution, workshops over design, and pseudoscientific frameworks over creating distinctive, lasting brand assets.

How did we get here? And more importantly, how do we return to designing brands that stand out and endure?

I challenge the cult of “brand love” and “brand strategy theater” with a powerful alternative: meaningless distinctiveness.

The Rise Of Brand Love

Driven by the pursuit of customer loyalty, the design industry is obsessed with an outdated distortion of brand strategy. This obsession is rooted in the theories of figures like Rosser Reeves, Jack Trout, and Kevin Roberts.

In the 1960s, Reeves discussed the Unique Selling Proposition, or USP. His idea was that brands should make clear and unique promises to customers to earn their loyalty. Trout, in his books Differentiate or Die and Positioning (co-written by Al Ries), took this further. He argued that brands must radically differentiate themselves to survive and that brands can “own” attributes and other associations, with loyalty as the reward. Then, in 2004, Roberts published Lovemarks.

Kevin Roberts spiritualized the business-centric approach of Reeves and Trout, framing emotional loyalty as a mission to “move the world” through love-inspired connections. Roberts elevated “loyalty beyond reason” to an almost sacred status.* He presented this idealized vision of customer devotion as the ultimate objective, the driving force behind successful brands, and a means of achieving world-changing influence.

*I unpack the moral implications of this framing here.

“Brand love,” in all its forms, reigns supreme in brand design today. Frameworks like “brand tribes,” “customer personas,” “onliness statements,” “brand purpose,” and “color psychology” are all deployed to serve the same objective: attracting an “ideal customer.”

Back in 2017, I fully bought into “brand love.” I shed my designer identity, adopting the roles of “brand strategist” and “brand matchmaker”—purportedly connecting brands with “the customer of their dreams.” Lost in the hype, I even considered outsourcing the actual design work—the reason clients hired me—to other designers.

But here’s the truth: Brand love, along with the loyalty myths it’s built upon, is a fantasy.

Like what you’re reading so far? I practice what I preach. Need a brand identity or name but don't need the usual dog-and-pony show that comes with it?

Brand Love Exposed

The focus on brand love has led to the misconception that customer loyalty is the ultimate goal. This is also fueled by the oft-repeated myth: “It's 10 times more expensive to get a new customer.”

In reality, most of a successful brand's revenue comes from customers who buy occasionally or infrequently, not from a small group of super-loyal customers.

In 1969, Andrew Ehrenberg discovered that brand purchasing behavior aligns with a statistical pattern known as the Negative Binomial Distribution (NBD) curve. The NBD curve in marketing illustrates two core principles:

Successful brands have very large numbers of light buyers, fewer medium buyers, and far fewer heavy buyers.

Those very large numbers of light buyers account for far more sales revenue than the very small numbers of heavy buyers.

This pattern holds for successful B2C and B2B brands and even nonprofit donor bases, over 3-5 years—even for brands Kevin Roberts would call "lovemarks."

While brand love theory champions targeting a small group of “ideal customers,” the NBD curve reveals a different truth: brands should target all buyers, especially the often-overlooked, infrequent, and distracted ones.

As Byron Sharp of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute often describes it, customer loyalty is more like a “polygamous” relationship than a monogamous one. Most customers “loyally”—or rather, habitually—buy from 2-4 brands in a category. Their brand choices typically depend on which brands are readily available. A strong sense of brand devotion or fandom rarely drive their purchases.

The case against brand love is based on real data, while the case for brand love relies mostly on stories and anecdotes. “Brand love” believers often focus on extreme examples of brand loyalty, like Coca-Cola collectors or Lego fans.

These stories are interesting, but they don't represent most customers. The typical customer story—”Dad buys Legos one Christmas, and not the next”—isn't very exciting.

Sure, some people are really into Subaru or Patagonia. My father-in-law has a Harley-Davidson tattoo! But most people buy a Subaru because it's practical, not because they love dogs or the outdoors. College students might wear Patagonia because it's fashionable, not because they care about the company's environmentalism.*

My dad, a motorcycle enthusiast but not brand-loyal, once found a great deal on a Harley. He mostly wanted to show off the novelty of its loud engine in his garage. He rarely rode it and eventually sold it. He's typical. My father-in-law, on the other hand, is the exception. He bought his Harley secondhand, likely from someone like my dad.

*It's worth noting that even though Patagonia might have some very loyal customers, brands like Nike, Columbia, Under Armour, and L.L. Bean sell far more fleeces by targeting all buyers.

To further contrast brand love with reality, let's look at two contrasting quotes. Seth Godin has consistently pushed brand love theory—even popularizing the term “brand tribes.” Bob Hoffman has been an outspoken critic.

Which quote sounds more like your own buying habits?

Quote #1:

“People don’t buy products and services. They buy relations, stories, and magic.” - Seth Godin

Quote #2:

“Here's how marketers think: How can I engage consumers with my brand and create a community? How do I connect the authenticity of my brand with my target audience? How can I co-create with my target and develop a conversation?

Here's how consumers think: Is there gonna be parking? Is this f*cking thing gonna work?

For the most part, consumers do not want to have a conversation with your brand, or an authentic relationship with it, or engage with it, or co-create with it, or spend a romantic seaside weekend with it.

Of course, brand preferences exist...but brand love is a juvenile fantasy…”

- Bob Hoffman from his talk ”Marketers are from Mars, Consumers are from New Jersey.”

The seductive allure of “brand love,” with its promise of deep emotional connections between brands and consumers, often negatively impacts design.

Chasing “ideal customers” pushes designers towards fleeting trends and stereotypes, which alienate many potential customers. This constant chase for what's “in” creates a homogenized landscape where brands all look the same and quickly become outdated.

Furthermore, this pursuit of "brand love" has fueled an industry-wide obsession with workshops and frameworks, which create a mirage of strategic depth.

I call this phenomenon “brand strategy theater.” Brand strategy theater is the performance of strategic processes—workshops, frameworks, jargon—that create the illusion of strategic depth while neglecting the core principles of effective design.

This “theater,” involving everything from “design thinking” workshops to Lego exercises, lulls designers and clients into a false sense of security.

The Rise of “Brand Strategy Theater”

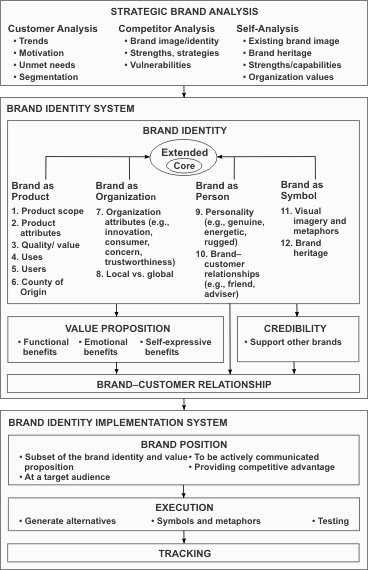

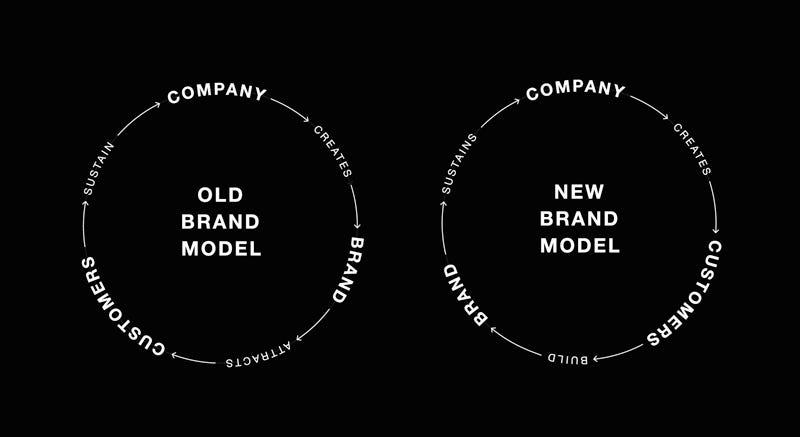

Today’s culture of brand strategy theater, at least within the design industry, has roots back to the late 1980s and early 2000s. Branding models like David Aaker’s Brand Identity Model (now called the Brand Vision Model) and Marty Neumeier’s The Brand Gap fundamentally shifted the design landscape by injecting brand strategy into a domain where it had previously played a minimal role.

Before Aaker’s work, brand strategy and design were separate fields. Brand strategists focused on positioning, messaging, and customer relationships. Designers handled visual identity and execution. Aaker’s Brand Identity Model changed that by introducing “Brand as Symbol,” placing design on the radar of brand strategists and, in turn, pushed designers to consider broader strategic concerns.

In the early 2000s, Neumeier’s The Brand Gap further solidified the connection. It claimed to “bridge the distance between business strategy and design.” Designers began seeing strategy as a golden goose. Neumeier’s later works introduced “design thinking” into branding, further cementing the importance of strategic exercises and a culture of “brand strategy workshops.”

While brand strategy is indispensable for overall brand building, guiding crucial decisions like messaging, positioning, distribution, pricing, and more, its direct application in the initial design and naming phases often proves counterproductive.

And yet, brand strategy has been elevated above idea creation and execution within the design process. Its integration has spawned a booming industry of workshops and frameworks, often adding layers of complexity where none is needed. Rather than improving brand design, the industry's fixation on a misguided version of brand strategy often undermines it.

The underlying issue is a set of flawed assumptions about brand strategy, assumptions that various thought leaders, including Marty Neumeier, have perpetuated.

The first flaw is the fixation on hyper-loyal customers, which pulls designers into a spiral of idealized audience profiles. These fictional consumers soon turn into stereotypes, with assumed tastes and aesthetics that justify generic, trend-driven design.

The second flaw is the assumption that brand strategy is static. Many treat it as something defined once and for all in a single workshop. However, these elaborate workshops often produce documents destined for the landfill. Real-world marketing quickly outgrows these theoretical exercises as brands evolve and expand.

These flawed assumptions, combined with the rise of “design thinking,” focus more on process than execution. This has created a perfect storm for “brand strategy theater,” churning out indistinguishable brands that fail to adapt to a dynamic market.

Even its most ardent supporters are not immune.

Chris Do, something of a disciple of Neumeier's and a vocal advocate applying brand strategy frameworks to design, ironically struggles to achieve distinctive results. He founded The Futur, the most influential educational resource for designers, and also runs the design agency Blind. In an attempt to demonstrate the branding process on The Futur's “Building a Brand” YouTube series, his agency, Blind, branded a brewery. The resulting logo, a clichéd hop design, underscores the limitations of these frameworks.

The team at The Futur fell into the same trap as many others influenced by these frameworks. They sidelined core design principles in favor of an overcomplicated strategy and an obsession with customer fandom.

In contrast, some of the most influential brand designers have designed iconic, enduring brands without adhering to rigid strategic formulas.

A 1991 Miggs B on TV interview with Paul Rand sharply contrasts with the “brand strategy theater” discussed earlier. As “Miggs B” searched for deep strategic meaning in the IBM and Westinghouse logos, Rand dismissed the over-analysis, emphasizing practical design decisions. The IBM logo has eight bars—not for symbolism, but because more would blur the lines and fewer would weaken the letterforms. The Westinghouse logo’s dots made an otherwise generic letter more distinctive.

This pragmatic approach is echoed by other leading designers: Pentagram partner Natasha Jen has dismissed design thinking as “bullshit,” both Michael Bierut and Sagi Haviv have articulated that great logos don’t usually have inherent meaning, and even Michael Johnson, designer and author of a best-selling book on brand strategy, critiques the workshop industry that has emerged over the last 20 years.

Their work demonstrates that lasting brand design isn’t the result of complicated strategy workshops or theoretical exercises. While brand strategy plays a vital role in other areas of business, true longevity in design comes from distinctive and timeless solutions that stand out and endure

The design industry's obsession with “brand strategy theater” is not just a harmless fad. It’s a fundamental misdirection. We are not only failing to create distinctive brands, but we are actively engineering a world of indistinguishable, forgettable, trendy, and ultimately ineffective brands.

Let’s examine some widely used strategies that, despite their popularity, often do more harm than good in the pursuit of strong brand design:

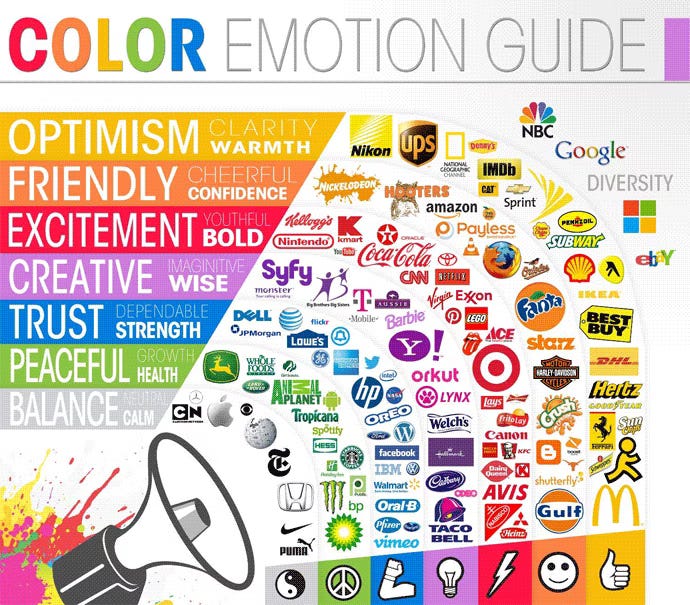

Color Psychology - Color Psychology suggests colors evoke specific emotions (e.g., blue = trust, red = passion). However, when competing brands apply this logic, they naturally appeal to the same emotional needs. This leads them to choose the same colors. As a result, brands within a category start to blend. This makes it harder for customers to distinguish one from another, such as the prevalence of blue in banking.

Furthermore, color connotations are also context-dependent and vary across cultures.

Lastly, advocates often force-fit brands into preconceived theories. This is evident in the numerous inconsistencies of widely circulated color psychology charts. For example, below Monster Energy is included under “peaceful,” Cartoon Network under “balanced,” Texaco under “exciting,” Twitter under “trustworthy,” and Harley-Davidson under “friendly."

Onliness Statements - Onliness Statements—Marty Neumeier’s concept, rooted in Rosser Reeves' USP and Jack Trout's Differentiate or Die—suggests that brands can achieve exclusive market ownership of a differentiator. For example, Harley-Davidson “owns” big, loud motorcycles. While marketing scientists have largely discredited this theory, it persists in the design industry, due in part to Neumeier’s The Brand Gap.

Mark Ritson’s “Relative Differentiation” offers a more realistic view. For example, Harley-Davidson is more associated with big, loud motorcycles than most. Yet, even this requires significant investment and can sometimes backfire. Harley’s fixation on “big and loud” has limited its success in foreign markets and the emerging EV space.

Ultimately, the differentiation debate is largely irrelevant to brand designers.

Brands change. Brand assets must endure. Onliness statements act like a straightjacket, forcing designers to hyper-target current positioning rather than future growth. So, when an inevitable shift occurs, a costly rebrand is required. Designers win. Clients lose.

Customer Personas - By relying on narrow, generational stereotypes within the identity design process, customer personas can limit a brand’s ability to connect with the broader category. This is true even if targeting a specific group initially makes sense, as it can hinder the brand’s potential to expand and resonate with a wider audience later.

For example, defining audiences by age often leads to an over-reliance on fleeting trends, like warped psychedelic fonts or “dopamine design” for Gen-Z and “boho minimalism” for Millennial women. This risks immediate alienation of higher-spending segments and long-term obsolescence as trends fade. Design trends also lead to short-term category sameness, as brands chase the same aesthetics.

Within individual communications to narrower segments like Gen-Z, design trends can be useful. However, this approach works only if core assets—such as logos—remain timeless. Timeless assets provide the flexibility needed for evolving marketing strategies while preserving a brand's identity and stability over the long term.

Ultimately, relying too heavily on personas that focus on narrow segments limits a brand’s broader market potential now and in the future.

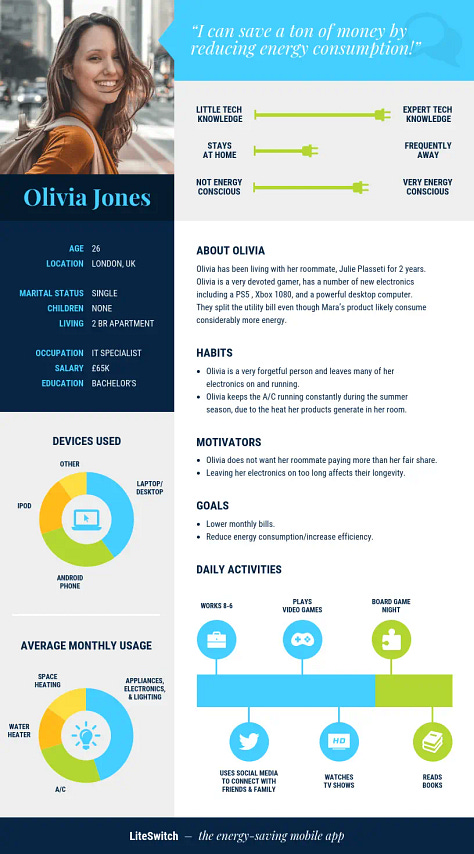

Screenshot of the customer persona from The Futur’s series Building a Brand, which resulted in a cliché brewery logo.

Our clients deserve better than “brand strategy theater.” We must adopt a simpler approach to brand design. This approach should be rooted in the fundamentals of distinctiveness and timelessness.

I suggest we replace “brand love” and its offspring, “brand strategy theater,” with a radically different approach: “meaningless distinctiveness.”

Looking for a distinctive and timeless brand? I’m currently seeking design and naming projects.

The Case For Meaningless Distinctiveness

Brand design isn’t about impressing or attracting attention—it's about being remembered.

Every exposure—whether on a store shelf, billboard, or social media—contributes to recognition, which builds trust and drives brand growth. Without recognition, consumers are unlikely to purchase.

But, not all brand exposures are created equal.

Recognition depends on distinctiveness. Generic brands blend in, requiring more exposure to build recognition, while distinctive brands stand out quickly and are easier to recall.

Research from the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute suggests that distinctiveness is the key to impactful brand design. The Institute defines “distinctive brand assets” as core elements that drive quick brand recognition, like jingles, colors, logos, and mascots.

In their book, Building Distinctive Brand Assets, the Institute argues that radical distinctiveness through audio and visual cues is vital for brand growth.

Few designers would dispute the importance of distinctiveness in brand design.

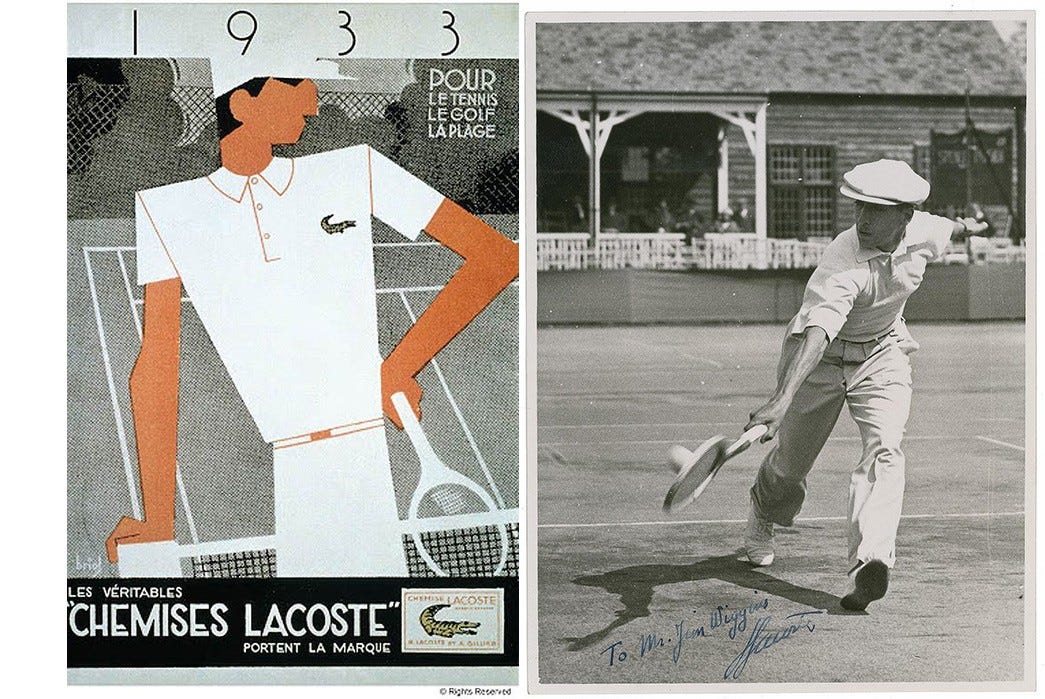

However, the Institute takes this concept further, advocating for “meaningless distinctiveness”—unexpected elements like the Geico gecko, the Lacoste crocodile, or the Coca-Cola polar bears. While these symbols aren't entirely meaningless (as all objects or animals carry some inherent significance), they are deliberately unrelated to their industries.

This approach allows brands to radically stand out in the market long-term, minimizing customer confusion and accelerating brand recognition. By using distinctive elements that don’t have obvious ties to the industry, brands can create a unique identity that is instantly recognizable.

Meaningless brand assets offer several key advantages:

Memorability. Meaningless assets cut through the clutter, making brands more memorable than those relying on category-related imagery.

Most designers are familiar with obvious examples of this, like spines for chiropractors and coffee beans for coffee shops.

However, even relying on entire design styles—such as hyper-masculine aesthetics for energy drinks and detailed illustrations for organic foods—can hinder memorability.

Longevity. Meaningless assets, by their very nature, are less likely to be considered by others, minimizing the chance of unintentional duplication from competitors.

Flexibility. Meaningless assets are not tied down to a single product offering or differentiator.

The lack of meaning between fruit and tech lets Apple effortlessly transcend specific products. Their logo adorns computers, phones, watches, VR headsets, and even credit cards. Simultaneously, Apple’s meaningless assets enable marketing campaigns to seamlessly transition from playful dancing silhouettes to serious fraud awareness initiatives.

Unlike “brand love” and “design thinking,” meaningless distinctiveness offers a more direct approach, allowing designers to focus on creating effective brand assets.

That said, some designers may still find frameworks helpful to spark creativity, and that’s perfectly fine—as long as the framework doesn’t take over the execution.

Even for brands focused on “brand love,” meaningless distinctiveness—think of the Apple name and logo or the Starbucks mermaid—can be a powerful visual foundation.

Meaningless Distinctiveness Strategies

Designing with meaningless distinctiveness doesn’t mean drawing random symbols from a hat. Strategy can still play a critical role.

Below are some tips and tricks that will significantly impact the effectiveness of meaningless assets:

Research your competitors’ design assets to ensure radical distinctiveness.

Research existing names and brand assets in your category (regional, national, and international) using Google Images and trademark databases. Avoid any conceptually similar ideas, even if you think your variation on the idea is unique. Be sure to check for available domain names when creating a brand name. Skimping on this research is a recipe for unoriginal—and potentially illegal—branding.

Look for asset ideas that are familiar, yet distinctive.

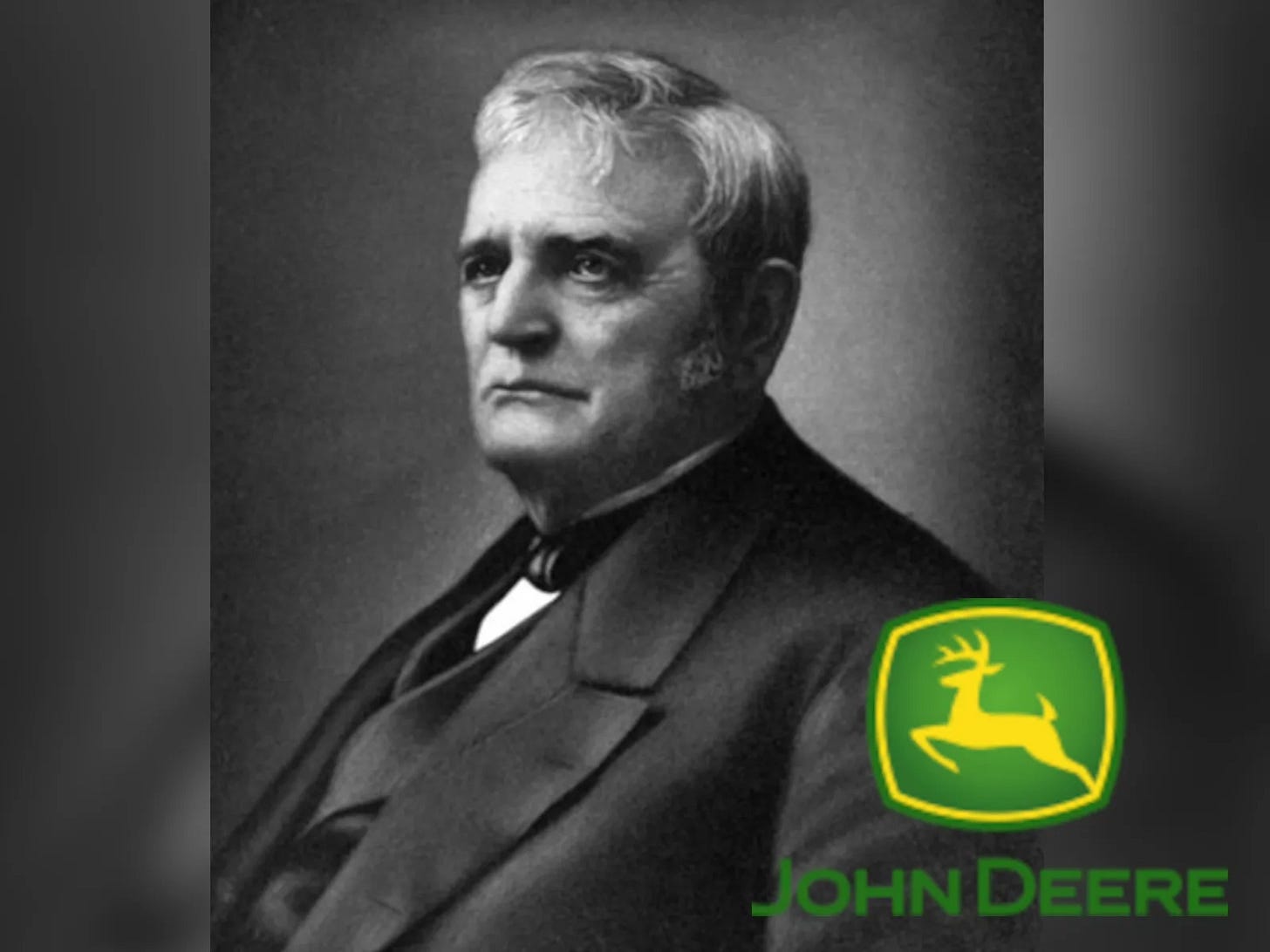

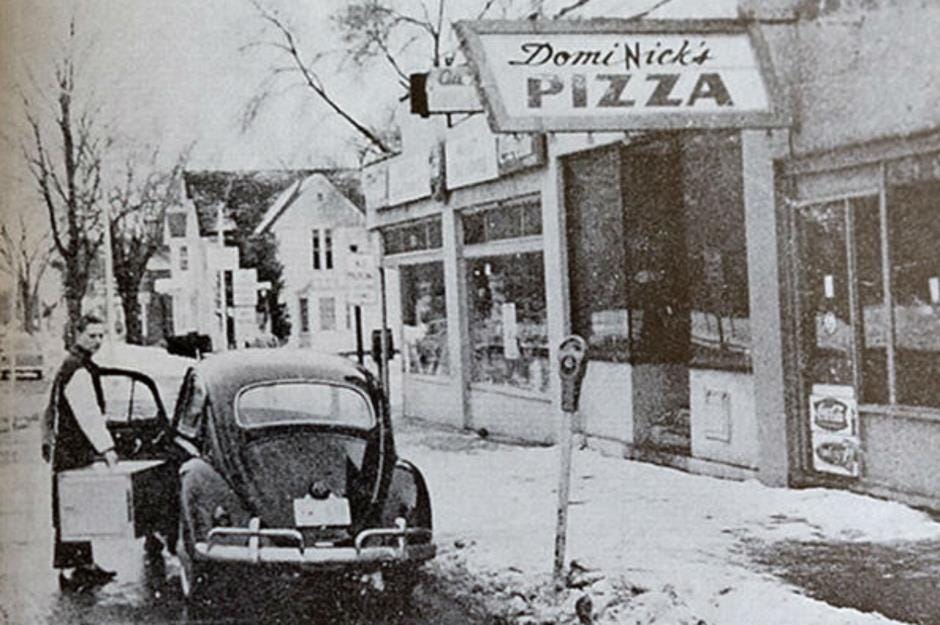

To achieve stronger brand recognition, leverage the power of familiar imagery—but in the unexpected context of an industry. Using familiar imagery like animals (Lacoste, John Deere) or objects (Apple, Domino's) in unrelated industries boosts memorability.

Aim for visual brand names where possible.

While established brands face limitations, building a brand from scratch allows for a visually representable name (e.g., Apple, Shell, Domino's, John Deere). This combination of name and correlating visual assets accelerates brand recognition.

Many iconic brands stumbled upon this powerful synergy by chance.

When the client is looking for meaning, get creative.

Designers and clients can have it both ways. Internal meaning in a brand asset can be powerful, as long as it’s not burdened by any inherent or intuitive link to the category. Gatorade's name is intertwined with the Florida Gators college football team, but many consumers don't know, forget, or don’t care.

Here are some other examples of “meaningless” assets with deep internal significance, as well as some that are much more random:

Mercedes Benz: For the Daimler brothers, the three-pointed star logo was sentimental. It originated from a symbol used in a postcard from their late father, to mark their home.

Wendy’s: Wendy’s was named after Dave Thomas’ red-headed daughter.

NBC: The NBC Peacock originally symbolized NBC’s venture into color TV. For obvious reasons, color is not significant to NBC’s positioning today.

Aflac & Geico: The Aflac Duck and the Geico Gecko were much more serendipitous. Both mascots stemmed from how their brand names sounded similar to a duck’s quack and “gecko,” respectively.

McDonald's: The McDonald’s arches were also serendipitous. Ray Kroc, seeking to make his restaurants stand out, instructed his architect to “design something unique.” This led to the distinctive yellow arches on their earlier buildings. After viewing the arches from an angle one day, Jim Schindler, head of engineering and design at McDonald’s, realized they formed the letter “m.” The iconic logo was born.

The inspiration for “meaningless distinctiveness” can be surprisingly diverse. My own creative process has involved exploring various avenues. Below are a few examples of names and distinctive brand assets I've developed for clients, along with the random inspiration behind them:

Trust yourself and your clients’ intuition to design appropriate assets for the brand.

By “appropriate”—a term I've borrowed from logo designer Sagi Haviv—I mean that the asset feels natural within the brand's context and doesn’t alienate potential buyers. This applies to logos, mascots, jingles, or other distinctive brand assets. Be careful not to conflate appropriate with meaningful or you may fall into the trap of a category cliché. The goal is simple: create something that fits—and for brand mascots, isn't too annoying.

Limit your use of Pinterest, Behance, Instagram, and other design inspiration sites to avoid design trends.

Avoid using popular platforms like Pinterest, especially for logos, as they prioritize fleeting trends.

Instead, study timeless design examples of graphic identities like those from Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv or Pentagram. For brand mascots, watch the ads of those that have changed very little over time (Geico, KFC, Hotels.com, Aflac, Energizer, Pillsbury, Michelin, Captain Morgan, Duolingo, M&M’s, Charmin).

As you can see, when I searched for “logo design” on Pinterest, most results were dominated by trend-driven logos—including boho minimalism and warped fonts—styles that are currently popular but fleeting in the ever-shifting world of design trends.

The work of Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv can be a great inspiration for timeless logos.

If you keep these basic strategies in mind, the world is your oyster. Even an oyster could be your oyster!

Our Clients Deserve Better.

The design industry has gotten tangled up in the fantasy of “brand love” and the performance of “brand strategy theater.”

We’ve spent too much time chasing trends and complicated frameworks, forgetting the basics of effective brand design: distinctiveness and timelessness. We’ve been sold on exclusive loyalty and perfect customers, only to realize that brand design success comes from recognition, not manufactured love.

The truth is, brand loyalty is more complicated than we’ve been led to believe, and long-term growth isn’t about catering to a few, it’s about reaching the many.

It's time for a course correction.

We need to move past the fluff of flawed frameworks and workshops that focus on the process instead of the design itself. Let’s ditch the pursuit of “brand love” and embrace something simpler but more powerful: “meaningless distinctiveness.” This doesn’t mean picking random stuff out of thin air—it means carefully designing memorable, unique brand assets that radically stand out, have broad appeal, and last.

By leaning into the unexpected, the familiar yet distinct, and the deliberately meaningless, we can create brands that get noticed and stick in people’s minds. It’s about going back to the fundamentals, cutting through the noise, and building brands that last.

We owe it to our clients to get this right.

They’re the ones who end up paying the price for all the buzzwords and empty frameworks that don’t deliver. It’s time we stop wasting their resources and company time on ineffective strategies and start building truly distinctive, timeless brands that work for them.

For more thoughts on brand design, advertising, and marketing, you can find me on LinkedIn.

Great article. Very challenging. I don't agree with some of the foundational thrusts of this, (meaningless distinction) but I do think that there is a huge problem with the analytical putting creative in a stait jacket and charging money and time to do so.

Really challenging read. As a brand strategist serving mostly b2b tech SaaS and ai-native companies, it’s “differentiate or die”. But that usually puts the pressure on brand strategy and not so much design. At the end of the day, they want the identity to follow certain tropes for fear of alienating “their ideal customer.” I agree that strategy should be the foundation of good brands(and can help build the meaning and lore today’s marketing leaders want), but it shouldn’t over reach to dictate it. I’ve done a lot of writing on flexible brand systems (strategy and design) and this drove it home for me: “In contrast, some of the most influential brand designers have designed iconic, enduring brands without adhering to rigid strategic formulas.” The TLDR: differentiation is king. Flexibility is a necessity. And a great brand sometimes just takes guts. A strategist should help get wary clients on board.