The Secret Stuff of Successful Super Bowl Ads

It's not entertainment, tugged heartstrings, or humor—it's distinctiveness

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of Woo Punch, a brand design studio rooted in marketing science.

I name brands and design identities (including logos, brand mascots, taglines, colors, sonic logos, and other fluent devices).

The Super Bowl Isn’t a LinkedIn Comment Section

This year, three ads had the marketing world buzzing before the game even started—Pepsi, Xfinity, and Claude. Marketers called them bold, differentiated, must-watch. Then the game happened.

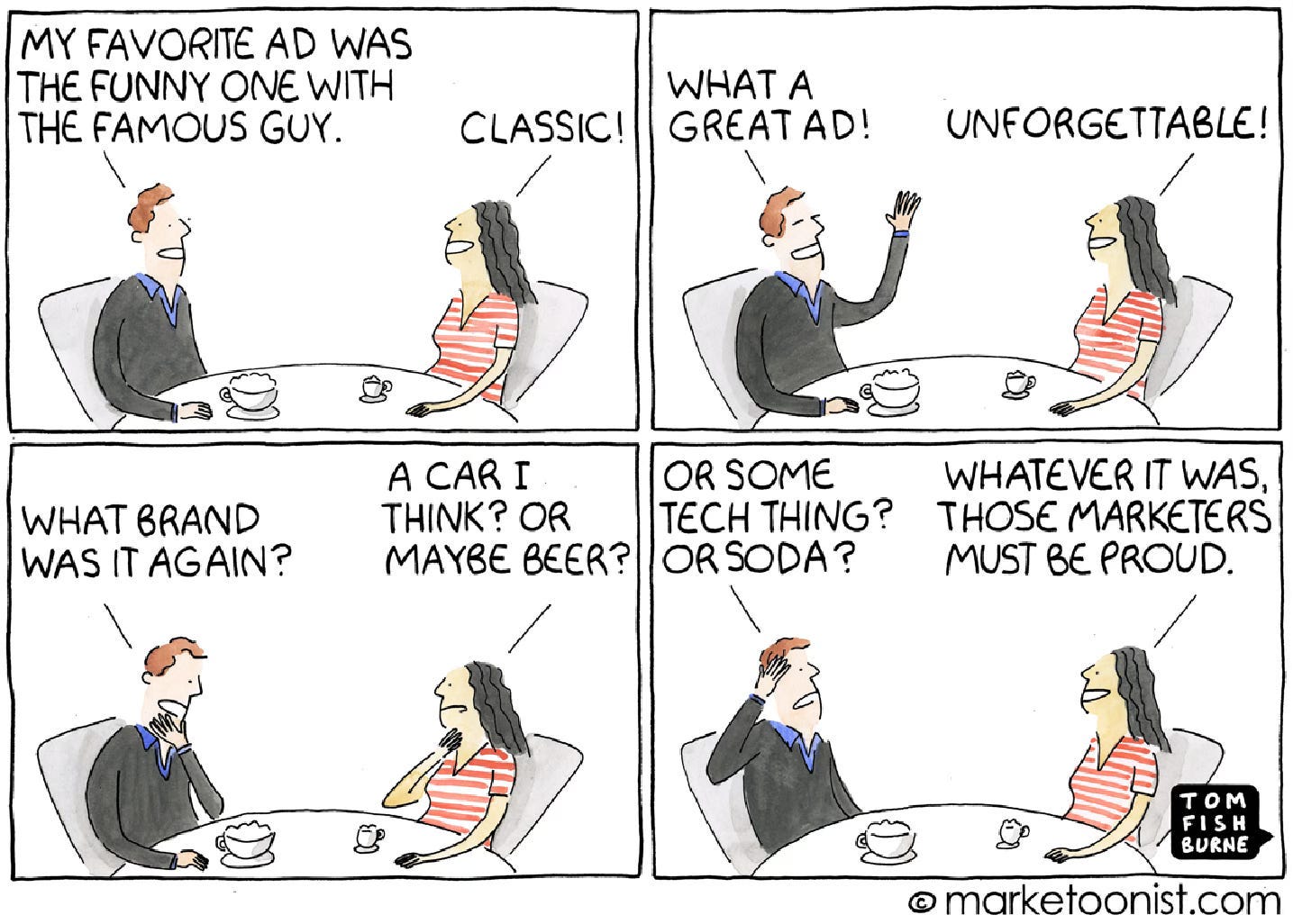

As my kids ran laps around the living room and my wife and I fed them dinner, I caught these ads in my peripheral vision—exactly how most viewers experience them. The ads that dominate LinkedIn don’t dominate the living room. You can't judge an ad from your desk chair with noise-canceling headphones. You can only truly test it with a distracted glance while someone throws food. That's the reality of advertising consumption, even for Super Bowl ads in 2026.

I remember Super Bowl parties where the sacred rule was no talking during commercials. Those days are gone (unless you’re a marketer). For years, Super Bowl ads have stopped entertaining and started trying to "matter"—desperate social purpose, glossy emptiness, nostalgic celebrities parachuted in with no humor and no point. We're battling devices, second screens, and fractured attention, and the ads themselves have surrendered. In the midst of it all, somehow, brands are still hiding their logos until the final two seconds.

Some respected marketing scientists are now saying we are too obsessed with distinctiveness. They say we need more entertainment, more emotion, and more creativity. I agree with the second part, but if this year’s most celebrated ads taught us anything, it is that we are far from being too obsessed with distinctiveness. Pepsi advertised its competitors assets and Claude followed the traditional Cannes Lions playbook: do everything you can to avoid showing your audience your brand.

Xfinity, meanwhile, hit the balance. Humor, nostalgia, attention, celebrity—and crucially, strong brand codes (given what they have to work with). If they commit to their spokesperson long-term, he could become the next Kevin Miles ("Jake from State Farm") or Milana Vayntrub (AT&T)—an ownable face that strengthens brand codes through consistent, exclusive association.

If the living room is chaos, if attention is fractured, if even Super Bowl ads can't command focus—how do you break through? The solution isn't louder. It isn't more emotional. It certainly isn't more "meaningful." The solution is designing for the moment when someone isn't paying attention at all. Because that's not the exception anymore. That's the default.

Design for the Most Distracted Brain in the Room

There’s a principle from physical product design worth borrowing: design for the extremes. Build a dish scrubber that works for someone with severe arthritis, and it works effortlessly for everyone else. The same logic applies to advertising. Don’t design for the average viewer. Design for the most distracted brain in the room.

As someone with ADHD, I am that extreme. My brain doesn’t pay attention to advertising—it scans for patterns mid-thought. For a brand to build familiarity with me, it can’t just be relatively distinctive. It has to be Category-Defiant.

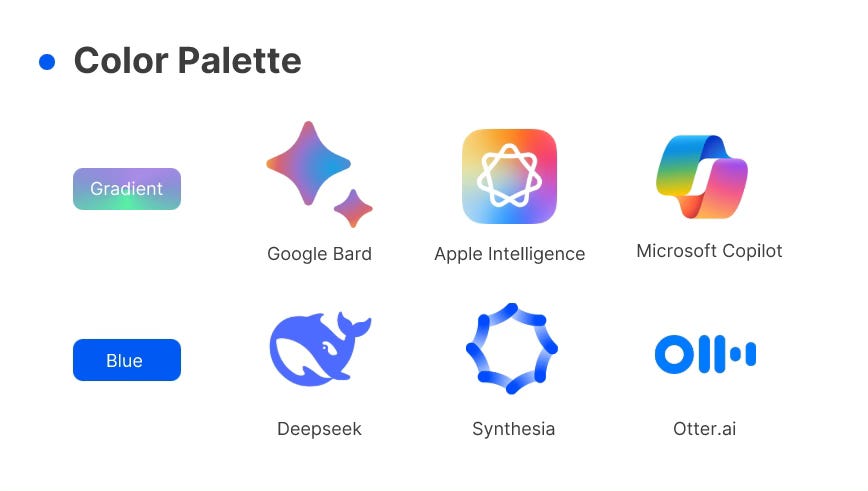

Category-Defiant Distinctiveness (CDD) means completely abandoning the visual sea of sameness that plagues your industry. Not a slightly more unique version of your competitor—something so visually unmistakable it bypasses the logical brain entirely. If every AI platform uses a spacey logo and color gradients, you go organic, orange and hand-drawn like Claude. If every energy drink brand is loud and hyper-masculine, invest in whimsical illustrations like Red Bull or Ghost.

You could even take it a step further: conquer the soda industry with polar bears, upend insurance with an emu, or dominate the pizza world by naming your empire after a parlor game.

Category-Defiant Distinctiveness (CDD) matters most for light buyers—the occasional and non-buyers who, according to the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, drive the vast majority of any brand's revenue. They function exactly like someone with ADHD: they aren't actively watching your ad, and even when they do pay attention, they won't buy for another three years. Which means repeated, distinctive exposure is the only thing building the familiarity that eventually triggers purchase. You don't need a clever message. You need an unmistakable visual hook that registers before the brain looks away.

Saturate the Screen With Your Brand

I loved Claude’s Super Bowl ad when I watched it on LinkedIn with headphones. In the corner of my eye during the game, the brand was invisible—teased out until the very end. If your concept relies on a generic-looking actor saying generic things while withholding the brand until the final seconds, you’re betting everything on full attention you’ll never get.

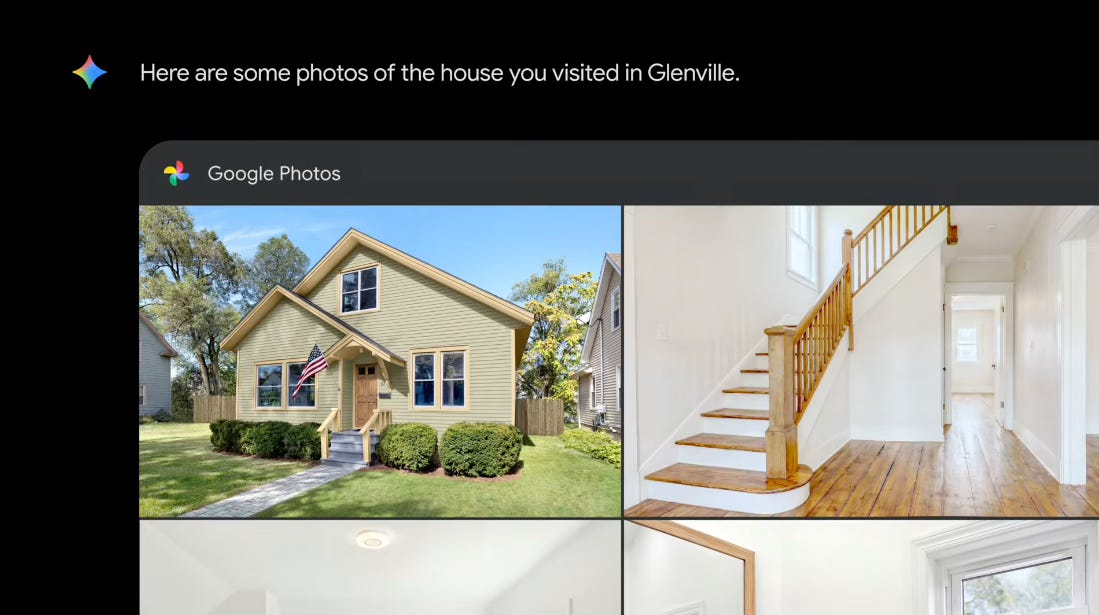

Compare Claude to Gemini’s ad, which takes place almost entirely inside their interface. They fabricated a fictional interface for the sole purpose of plastering “Google Gemini” throughout the ad—and then smartly incorporated Google Photos, a far more familiar brand, to ensure no one mistook it for ChatGPT or any other competitor. They also wrote the ad as if no one in the audience had ever used Gemini before.

Xfinity’s Jurassic Park ad is the goal. Compare it to Volkswagen’s “The Force” from 2011. Both leveraged beloved films. Both made you feel something. But Xfinity wove their brand into the concept itself—the story only works because of Xfinity. VW teased theirs until the end, and most viewers never even made the connection. Xfinity had a fighting chance to be remembered. VW gave away memory for admiration.

If your idea only works by hiding your brand (or showcasing your competitor’s brand), it's the wrong idea. The best creative minds get Super Bowl gigs precisely because they can work within constraints. Ads aren't Oscar bait—they have to sell. That's what makes them more creative than short films, not less. Real creativity thrives in constraints. Short films just need to entertain. Ads need to entertain and move product. That's harder.

This Applies to You

You probably aren’t running Super Bowl ads. But the rules don’t change by budget size—they get stricter.

Massive brands can survive some of these mistakes. Pepsi will be fine after inadvertently promoting Coca-Cola to millions of distracted viewers. But if you’re a smaller brand, you can’t afford to hide yourself and you can’t thrive on a generic identity. Invest in a category-defiant brand. If you’re established, add a category-defiant asset—a mascot, a visual signature, something that refuses to blend in. You can survive with a generic name or logo, but only if something else in the mix is unmistakable. I help brands build exactly these things: names, logos, mascots, and other distinctive assets designed to cut through the noise before the brain has a chance to look away.

The living room is the jury. Not LinkedIn.