"Meaningless Distinctiveness": 20 Examples and Their Backstories.

Lions and Nazis and "Mother McDonald's Breasts," Oh My!

What is “Meaningless Distinctiveness?”

Before we get into examples, let’s talk about meaningless distinctiveness—because it’s often misunderstood.

When the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute talks about meaningless distinctiveness, they are referring to distinctive brand assets—logos, colors, mascots, jingles—and names* that stand out precisely because they seem randomly chosen or disconnected from the category.

The goal is to build brands so distinctive no competitor can—or would even think to—copy them. Imitation isn’t always deliberate. Assets that feel unnatural or irrelevant to the category are less likely to be mimicked, even by accident.

*Ehrenberg-Bass doesn’t specifically include names in its discussion of “meaningless distinctiveness,” but the same logic applies.

The issue is that both “meaningless” and “distinctiveness” get twisted (even Jenni Romaniuk of the Institute believes the term “meaningless” falls short).

Meaningless doesn’t mean “no meaning”—it means “no category meaning,” and often no business meaning at all.

Everything has meaning. “Meaningless” here just means no meaning in a market context. For example, apples have no obvious link to tech—even if plenty of people, including Apple themselves, have tried to connect the two after the fact.*

*There are plenty of myths about Apple’s name and logo, but they are all post-rationalization. According to Steve Jobs’ biography, he chose it after visiting an apple orchard while on a fruitarian kick. He liked that it was “fun, spirited, and not intimidating.” That’s it. Apple only made the knowledge connection after picking the name, with their first Isaac Newton logo. Less than a year later, they scrapped it—and never went back to that idea.

Additionally, designers often claim “the logo’s simplicity reflects the product’s simplicity.” In reality, it’s simple because they hired a designer who understood that simple logos work. That’s true across the board—iconic logos tend to be simple, and most logos get simplified over time.

Distinctiveness isn’t differentiation, and it’s not at odds with it.*

Distinctiveness is about unmistakable brand assets—like the Geico Gecko, Lacoste’s crocodile, Wendy’s name/square patties.

Differentiation is about perceived differences (features, benefits, positioning, personality, pricing, etc.)—like Geico’s playfulness, Lacoste’s polo association, Wendy’s “fresh never frozen” line.

While both can contribute significantly to brand growth, distinctiveness has one particular advantage over differentiation. It is legally ownable. Geico owns its gecko, Lacoste its crocodile, and Wendy’s its name. By contrast, Geico’s playfulness used to stand out—now every insurer tries it. Lacoste invented the polo shirt—but today, they’re one of many brands making them. Wendy’s tagline was stolen from KFC.†

Other factors—timing, scale, distribution—matter more than meaningless distinctiveness, and differentiation can drive growth. But brands with some level of meaningless distinctiveness dominate Interbrand’s Top 100 for a reason. It’s durable, memorable, and hard to copy.

Now to the examples.

*Some frame distinctiveness and differentiation as either/or, but meaningless distinctiveness can reinforce any differentiation strategy. Even the “brand love” crowd can’t deny that many of their favorites—Starbucks, Apple, Suburu—lean on meaningless distinctiveness.

†It’s significant that Wendy’s blatantly stole their tagline from KFC because burger chains don’t just compete with other burger chains—they compete with chicken, pizza, and coffee shops too.

Famous Examples of Meaningless Distinctiveness:

1. The Lacoste Crocodile:

In 1923, Lacoste’s tennis star founder René Lacoste bet his coach he could win a crocodile skin suitcase after a Davis Cup match in Boston. Later, a journalist referred to him as “the crocodile.” The symbol stuck.

2. The Coca-Cola Polar Bears:

The Coca-Cola Polar Bears were first used in a 1922 French poster of a polar bear giving the sun a cold Coca-Cola. This was likely a strategic choice to emphasize Coke as a cold drink on a hot day. However, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, the polar bears shed their original message and took on the meaning of Christmas. The exact opposite of a hot day. Since their transition into a Christmas symbol, there is no link between the iconic polar bears and its category.

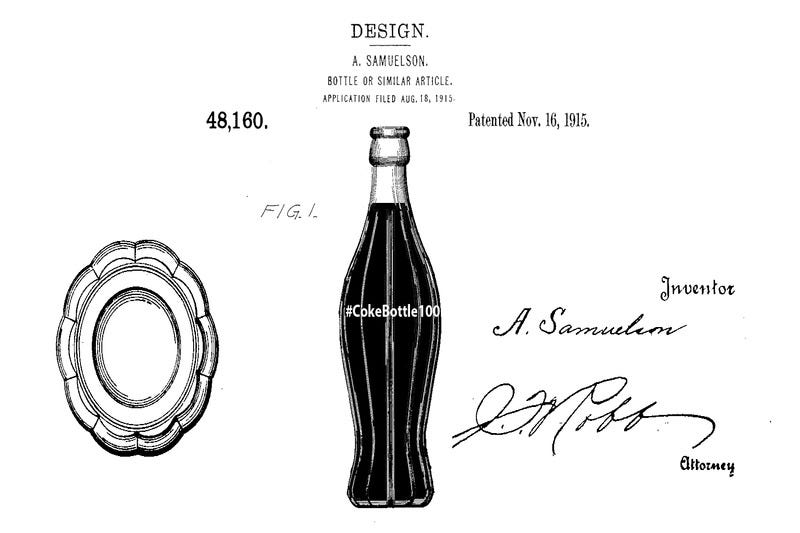

3. Coca-Cola’s Bottle Shape:

Speaking of Coca-Cola, they have always been at the forefront of distinctiveness for distinctiveness sake. In 1915, they asked bottle manufacturer, The Root Glass Company, to design something “so distinct that you would recognize it by feel in the dark or lying broken on the ground”.

Now that’s a proper design brief in my opinion.

4. The Geico Gecko:

GEICO stands for Government Employees’ Insurance Company. In 1999, the creative team at Martin Agency was hired to create a “mental shortcut” for the brand.

According to Per Neel Williams, SVP and group creative director at Martin, the Geico Gecko wasn’t intended to endure as a distinctive brand asset long-term. It was an idea for a single campaign.

“It was just, ‘Oh, Gecko sounds like Geico.’ The original concept was about the Gecko being annoyed because people kept calling him thinking he was Geico and they were trying to get car insurance.”

Since then, Martin Agency has spent 30 years helping Geico reinforce the gecko. Originally created for car insurance, the mascot’s meaninglessness makes it easy to stretch across products—car, motorcycle, home, even pet insurance.

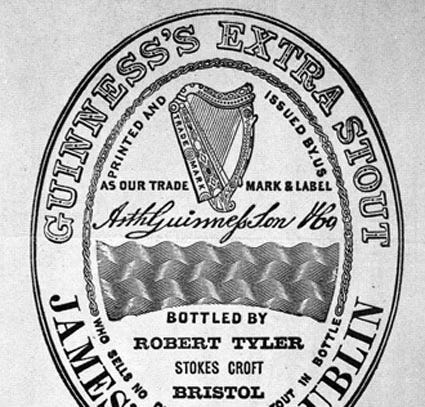

5. The Guinness Harp:

The harp has been a symbol of Ireland since the 13th century. In 1862, Guinness based their logo on a specific 14th century harp called the “Brian Boru Harp” to honor their Irish heritage.

Ironically, the Guinness harp, a symbol steeped in Irish history, now adorns Guinness Blonde American Lager, a testament to the adaptability of brand assets that have become meaningless for most over time.

6. The MGM Lion:

A publicist for Metro Goldwyn Mayer, Howard Dietz, chose the MGM lion as a nod to his alma mater, Columbia University. 6 lions have served as the mascot since 1916.

7. “Jake from State Farm” and the State Farm Sonic Logo:

The original “Jake From State Farm” was a real employee of the company, Jake Stone. Like the GEICO gecko, “Jake From State Farm” was meant to be a one-off character until State Farm hired an actor, Kevin Miles, to transition “Jake” into a distinctive brand asset.

“Jake from State Farm” is not their only distinctive brand asset aside from their logo.

In a stroke of genius, State Farm’s cliché jingle of the 1980s (“Like a Good Neighbor State Farm Is There”) has evolved into a campaign in the 2000s featuring customers singing the jingle’s lyrics before an agent magically appears. Today, the jingle is now a timeless sonic logo, paired with Kevin Miles speaking the lyrics.

8. Colonel Sanders:

Harland Sanders had a tumultuous career marked by numerous brawls, a literal shootout with a competitor, business ventures, and several shifts in employment. Despite his roller coaster of tensions with others, in 1935, he was commissioned as a Kentucky Colonel, a title awarded for his local popularity. After bouncing through various failed ventures, he eventually found success franchising his fried chicken recipe, founding KFC, which grew into a global brand.

“Colonel Sanders” understood showmanship, distinctiveness, and consistency. He began leaning into his title of colonel in 1950 and began dressing as a “southern gentleman.” He wore the same outfit every day in public during the last 20 years of his life. He even dyed his mustache and goatee to match his hair.

Since his death in 1980, KFC has turned the real-life Colonel into a rotating brand mascot. His image has been repackaged as everything from a cartoon to a marketing gimmick, played by a revolving cast of celebrities—Jim Gaffigan, Ray Liotta, Jason Alexander, even Reba McEntire.

9. The Budweiser Clydesdales:

The original Budweiser Clydesdales came from Shea’s Brewery. August A. Busch Jr. bought them in 1933 after Shea’s had used them to promote their own beer.