Branding Bullsh*t Is Not Harmless.

My family's 101-year-old restaurant and the consequences of bad advice.

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of Woo Punch, a brand consultancy rooted in evidence-based brand design. I write about the evidence that debunks brand purpose, differentiation, brand love, loyalty marketing, customer personas, color psychology, mission statements, customer engagement, AdTech, and “hustle culture.”

Want to chat about your brand? Schedule a free intro call.

What If My Family Listened To Branding Bullsh*t?

In 1919, my great-grandfather, Charles August Franke, bought a hole-in-the-wall donut shop in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and called it Franke’s.

By 2020—101 years later—Franke’s had closed its doors for good.

Born and raised in New York, “C.A.” trained for WWI in Arkansas before heading off to fight. He fell in love with the state and promised himself that if he survived, he’d come back.

C.A. was the son of a spark plug manufacturer who immigrated from Germany, but he saw the writing on the wall—mass production was about to crush smaller, independent shops like his father’s. After the war, true to his word, he returned to Arkansas and bought that donut shop. No one knows why he picked a bakery of all things (he wasn’t a baker), but that tiny storefront grew into a bustling business, expanding to multiple retail outlets and even delivering bread around town

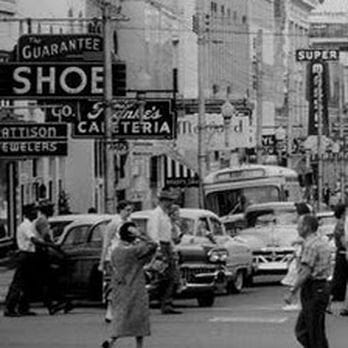

By 1924, riding the wave of his bakery’s success, C.A. pivoted to a new trend sweeping the country: cafeterias. He opened Franke’s Cafeteria in downtown Little Rock, and it quickly became the go-to spot for shoppers heading to “the city.”

The bakery was eventually sold off, but the cafeteria thrived—passed down from C.A. to my grandfather Bill Sr. and C.A.’s son-in-law Dick Lewis, followed by my father Chris and his brother (also named Bill) who ran 3 locations. In 2005, my dad sold his shares to my uncle.

Bill intended to pass the restaurant down to his daughter, Christen, continuing the Franke’s legacy into its fourth generation. But in 2016, Christen died unexpectedly, and less than a year later, Bill followed. The cafeteria was left to his wife, Carolyn, who kept the business running for three more years. But the toll of her grief, combined with the burden of managing the operation, became unbearable. She had no option but to sell in 2019.

Under new ownership, Franke’s shut down during the first year of COVID and never reopened—marking the end of a family legacy that had endured wars, depressions, and generations, only to be undone by loss and a pandemic.

When Branding Bullsh*t Meets Real Businesses

Branding bullshit didn’t kill Franke’s—but it could have.

I can’t stand the thought of a “brand strategist” swooping in to charge my grieving aunt—desperate to keep the restaurant alive—tens of thousands of dollars, only to tell her:

“The script font in Franke’s logo might’ve been popular in the ’20s, but it needs a redesign to stay relevant for your ‘target audience.’”—as if 100 years of built-up brand recognition meant nothing.

“Franke’s sounds outdated. Have you considered something more modern, like ‘Gather & Graze’ or ‘Urban Bites’ to appeal to a younger crowd?”—as if a century of name recognition is a problem to be solved.

“People expect a modern customer journey. Let’s ditch the tray line and add mobile ordering or self-serve kiosks.”—gutting the cafeteria of its entire business model and the primary reasons many customers ate there—a bit of variety and nostalgia.

And, inevitably: “What’s your brand archetype? Is Franke’s more ‘The Caregiver’ or ‘The Everyman’?”—as if a 100-year-old restaurant with a rich history could be defined by an oversimplified label.

Most brand designers work with smaller companies—companies that could survive or collapse, succeed or disappear, all based on the advice of a brand designer or strategist.

Our clients pour everything into their businesses. Some have built them over generations. Others scrape together a budget they don’t even have just to hire us, betting on us to help launch their company. Who are we to hold their futures hostage for weeks, months, or even years of strategy and design, only to send them into the market armed with recycled advice from branding books by self-appointed experts? Or worse: LinkedIn carousels?

Tropicana can botch a redesign and survive. SurveyMonkey can change their name, realize what a dumb move it was, and change it back—and remain a market leader.

A family-owned cafeteria with three locations, a local real estate agency, or a solo entrepreneur who sank their life savings into a dream doesn’t get that luxury.

In our industry, we laugh off bad branding advice as nonsense. The debates stay inside our echo chambers. Meanwhile, our clients feel the fallout. Bad frameworks, bad strategy, and bad design don’t just stay on the whiteboard—they have real-world consequences.

That’s the weight of the work we do.

Franke’s in Pictures Continued.

Thanks for sharing what is an inspiring and also very tragic story.

I agree with your general point, but the examples of what a self-proclaimed strategist would have said are obviously really bad. So yes, bad strategy is... well, bad. I am interested in your take on what a good strategist would have done.