A World Without Branding & Advertising

A world without branding & advertising might seem like a utopia, but I wouldn't want to live in that world.

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of Woo Punch, a brand consultancy rooted in evidence-based brand design. I write about the evidence that debunks brand purpose, differentiation, brand love, loyalty marketing, customer personas, color psychology, mission statements, customer engagement, AdTech, and “hustle culture.”

Want to chat about your brand? Schedule a free intro call.

Recently, consumers have become fed up with branding and advertising. This is understandable. Advertising today is more manipulative than ever, and there’s more of it. And branding often persuades us to spend more on lower-quality products. But, the only thing worse than a world full of branding and advertising?

It would be a world without it.

Imagine a world without branding and advertising. How would we decide which brands to buy? How much more time would we spend deciding between brands? How would we know how to quickly trust one brand over another?

We don’t have to imagine this world. Instead, we can simply look back in history.

THE WORLD BEFORE BRANDING & ADVERTISING

It’s 1930 in Queens, NY.

A new grocery store just opened with a whopping 6,000 square feet of shelf space! Thousands are lined up just to glimpse this behemoth they’ve read about in the newspapers. Upon entering, people feel faint and dizzy, entirely overwhelmed by all the choices. 16 years later, when a similar store opened in Rome, one woman is seen running up and down the aisles, screaming: “It must be heaven! There are mountains of food!”

This new “supermarket” experiment was less than half the size of a typical Walgreens today. The idea for the supermarket was first conceived by Michael J. Cullen, a branch manager for the grocery store chain Kroger.

Cullen wrote a letter to Kroger’s then-Vice President, claiming he had an idea to make Kroger “the greatest chain grocery store on the face of the earth.” Unfortunately, Kroger refused to listen to the lowly branch manager, so Cullen set off on his own, establishing the first supermarket. He dubbed it King Kullen, and it was an instant success.

Kroger eventually copied Cullen’s idea, becoming the second-largest supermarket chain behind Wal-Mart. But before that, another grocery store beat them to it—copying Cullen’s model within four months of King Kullen’s opening.

King Kullen bought that chain, and the sale funded its owner’s next venture—helping him build a household name: Trump.

The Trump family’s fortune began when Donald Trump’s father, Fred Trump, copied Cullen’s idea, sold the chain to King Kullen, and used the profits to invest in real estate.

Today, the only time we see people feeling faint in the aisles of grocery stores 6x the size of King Kullen, there’s a toilet paper shortage. So what happened between 1930 and today?

Branding and advertising.

HOW BRANDING & ADVERTISING HELPS US AS CONSUMERS

By 1930, branding had been around for a long time, but advertising was still in its infancy. As a result, consumers had more choices than ever, and those choices were, for the most part, well-branded (primarily because there were so few brands that it was easy for them to stand out). But without widespread advertising, consumers still weren’t familiar with most brands on supermarket shelves.

Radio ads were only 8 years old, and it would be another 8 years before the first television ad aired. Advertising hadn’t familiarized shoppers with the new brands introduced by the supermarket.

In 1930, there were only 2-5 total brands of tomato sauce on grocery store shelves, yet people dropped like flies, overwhelmed by all the choices. Today, there are over 50 tomato sauce brands at my local supermarket!

Widespread advertising and distinctive branding allowed shoppers to quickly scan grocery store shelves for familiar brands and filter out unfamiliar brands. As a result, despite over 50 brands of tomato sauce at my local supermarket, I only look at the 2-5 brands I recognize.

Next time you’re in the grocery store, count all the brands of tomato sauce you didn’t notice the last time you bought tomato sauce. You will see that your brain is highly efficient at filtering out unfamiliar brands. Of course, we filter out brands we don’t recognize and brands we do recognize but haven’t thought of in a while.

Another great example is cola. When looking to buy cola, we typically only notice brands like Coke or Pepsi. This is because Coke and Pepsi advertise to us more than any other cola brand. Coke and Pepsi also usually take up the most shelf space. However, if we stop and look closer, we might notice brands we’ve never heard of or even recognizable brands we missed at first glance, like Jones Soda, Rite Cola, or Tab. By filtering out brands, we can spend far less time in the grocery store.

On rare occasions, when we have plenty of time to shop, we might be persuaded to buy a brand we’ve never heard of based on its novel packaging, ingredients, or unique flavor. But this is the exception to the rule for most consumers when buying from most categories and in most buying situations.

In short, branding and advertising are the reason shoppers don’t feel faint today. But despite branding and advertising being helpful tools that allow us to spend less time shopping, many people want them done away with.

THE RECENT RISE AGAINST ADVERTISING

Some types of advertising should be done away with, in my opinion. For example, online advertising has recently gotten a lot of heat as a tool to manipulate our behavior. And not just our purchasing behavior, but other behaviors as well. Social media algorithms prioritize users’ addiction to sell advertising over connecting people in meaningful ways.

Online advertising is also accused of invading our privacy by monetizing our data so advertisers can target us more specifically. Ironically, this method of hyper-targeting is less effective. Online advertising can also be bad for advertisers because the industry is packed with ad fraud.

I think these tactics should have no place in advertising, but the solution isn’t to throw the baby out with the bath water. Overall, advertising is still a helpful tool for consumers.

THE RECENT RISE AGAINST BRANDING

Whereas advertising has always gotten a bad wrap from the same consumers who turn around and use advertising to make their lives easier, branding hasn’t historically been a cause for protest until recently.

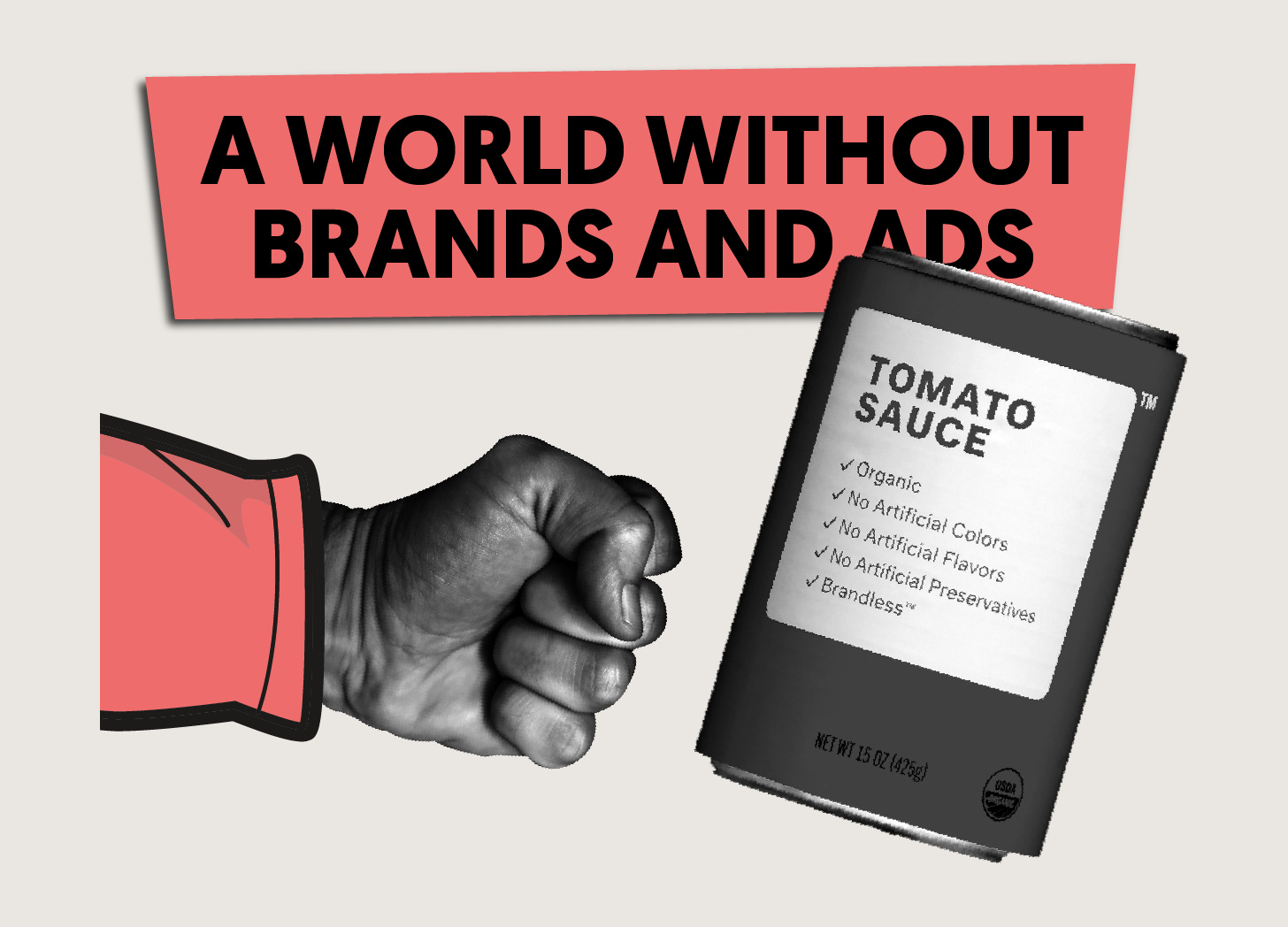

In 2017, a “revolutionary” company was formed that vowed to fight branding. Tina Sharkey, the founder of Brandless, claimed that consumers were fed up with brands. Not advertising. Brandless never explicitly stated that consumers weren’t bothered by advertising, but they did spend a lot of money on it themselves. Sharkey’s beef is with branding, not advertising.

Sharkey made the case that “grocery products contain a ‘Brand Tax,’ which can be up to 40% of what the item costs, to pay for the premium status and branding of that item.” As a result, Brandless’s products were generically labeled. For example, their shampoo label simply said “Shampoo,” and their toilet paper was labeled “Bathroom Tissue.”

Ironically, by appearing “un-branded,” Brandless products were branded. Every Brandless product was under the banner (AKA brand) of Brandless.

Brandless started as an online retailer where their products were only accessible on their website (which was branded). Then, like most eCommerce companies eventually figure out, being exclusively online wasn’t a sustainable business model for growth. So as they ventured into brick-and-mortar retail, they ran into the same problem every retailer in history has come up against.

They needed a brand. So, what did they do? They plastered their Brandless logo on all their products... Ultimately, they went back on their original promise to give consumers what they thought they wanted: “un-branded” products. Honestly, you can’t make this shit up!

What Brandless failed to realize is:

Consumers are willing to pay a premium for brands because they help us spend less time shopping.

The very nature of branding is inherent in all products (even generic store brand products are branded).

Consumers were not interested in an “un-branded” product line unless that product line was under a familiar store brand like Amazon, Kroger, or Wal-Mart.

How do I know consumers weren’t interested in Brandless’s “un-branded” gimmick? After a ton of initial hype, and a $240 million investment by SoftBank (the same bank that notoriously invested in the brand, WeWork, which “cooked the books” to fool investors), Brandless shut down in February of 2020 (before the pandemic).

Whether we admit it to ourselves or not, we all want branding and advertising as consumers.

Yes, they can be used to manipulate our behavior.

Yes, they often interrupt our lives.

And yes, they can be highly annoying.

But are branding and advertising “evil?” I certainly don’t think so, or I wouldn’t be in this industry as a practicing Catholic. I, for one, am thankful for branding and advertising.

I’m thankful I don’t have to spend hours in the grocery store.

I’m thankful I can hear about new, better products than the ones I currently use without subscribing to countless industry blogs.

I’m thankful I don’t have to research every brand in a category to find out which one is the best, cheapest, most enjoyable, or most trustworthy.

But most of all?

I’m thankful I can spend time thinking about more important things like:

Is my family happy? Do we need to cut spending this week? What errands do I have to run? When will I have time to pray today? Is my family ready for our new baby due in March? How can my wife and I raise our two daughters to know their worth and not fall prey to society’s expectations?

If you feel guilty about being a marketer, or you’re tempted to curse marketers for constantly trying to sell you products, don’t. Embrace branding and advertising (at least as long as it doesn’t employ harmful tactics). They’re not going anywhere, making our lives a whole lot easier.